The progressive case for tackling the risks of end-to-end encryption

There’s a progressive, positive human rights case for regulatory guardrails. It’s time we make it.

It’s time to reclaim the progressive case for mitigating the risks posed by end-to-end encryption.

For too long, privacy, data rights and tech libertarian voices have been able to frame proposed online safety legislation as regressive and running contrary to good human rights outcomes. As opposition to legislation has stepped up, we’ve heard an endless barrage of use cases that will seemingly be put at risk if we also act to protect children from preventable harm – LGBTQ+ groups, dissidents, victims of domestic abuse to name but a few.

It’s time to unpack these claims and state the progressive, positive human rights case for sensible guardrails on the rollout of end-to-end encryption. It simply isn’t progressive to pit the needs of one group facing potential vulnerabilities against another, nor to encourage marginalised groups to view encryption mitigations as a false choice between their privacy and safety.

And it certainly isn’t progressive to choose to expose children to inherently preventable harm that may result in lifelong trauma and negatively impact their life chances.

It may be convenient to frame online abuse as a societal problem, not a technological one, but externalising the problem isn’t legitimate – it’s a way to deflect attention from the need to tackle a complex and challenging issue, and from the imperative to develop and incentivise technical solutions that can protect the fundamental rights of everyone involved, including – unapologetically - children.

Opponents of regulatory safeguards are propagating a false choice

So much of the established end-to-end encryption framing relies on viewing this issue as a set of fixed binaries.

As opponents of legislation would have it: we can protect adults but not children; we can protect privacy but not safety; and any technical solutions or legislative requirements that incentivise them inherently mean weakening end-to-end encryption and putting vulnerable and disempowered users safety at risk.

But it’s time to call out these false choices for exactly what they are.

At its core, the Online Safety Bill is proposing a compromise approach: using client-side scanning to identify child abuse images before messages are end-to-end encrypted. The technology is purpose-limited and could not be extended to serve other use cases without entirely new primary legislation being enacted.

And despite claims that the technology doesn’t even exist (one tech libertarian researcher told BBC News last week that we ‘can’t rely on wishful thinking that technology companies can pull easy shortcuts out of thin air, and as a matter of fact at the moment these technologies simply don’t exist’), the reality is that client-side measures do exist and can work – in fact, they’re already used by WhatsApp for other use cases such as fraud and malware detection.

And although Apple decided not to proceed with its Neural Hash technology because of the ferocious backlash from privacy advocates inside and outside the company, company insiders have told me they are confident the technology is effective and robust. The working assumption is that this tech will have to sit on the shelf until there is legal and regulatory cover for it to be rolled out.

We’re therefore left with a compromise position that is technically deliverable but which privacy activists view as philosophically incompatible with end-to-end encryption.

As a result, some leading industry and privacy figures choose to make highly specious claims about the reliability and potential negative impacts of technical guardrails being imposed, choosing to point to a never-ending set of hypotheticals and slippery slope arguments that could never realistically be satisfied.

But the simple fact is that there is no other obvious route to balance the fundamental rights of everyone; no compromise-free means to balance the competing interests of a range of vulnerable groups; and certainly no way in which everyone can be satisfied 100 per cent.

The very nature of issues such as this is that they can only ever be resolved through compromise.

So instead we are left with privacy activists making a deeply circular argument that is increasingly disconnected from the technical solutions that are being proposed.

Furthermore, we are encouraged to believe that the only progressive solution is for tech companies to be somehow trusted to make their own decisions about how their products uphold fundamental rights, with free agency for tech libertarian and owner interests to privilege certain fundamental rights over others, and to decide which use cases are worthy of having their fundamental rights upheld.

One viewpoint doesn’t have a monopoly on progressive use cases

One of the most frustrating aspects of the current debate has been the way in which industry and privacy activists continue to claim that only unchecked end-to-end encryption can deliver progressive outcomes, and that any introduction of client-side scanning must inevitably result in regressive and societally dangerous outcomes.

In continuing to argue that client-side scanning represents a fatal flaw in the privacy protections so important to many vulnerable groups, privacy activists are conflating hypothetical risks as seeming inevitabilities.

Worse still, this narrative seeks to weaponise the legitimate concerns of a range of highly marginalised and vulnerable groups, encouraging them to see a false choice between their online and offline privacy and safety. Privacy activists are weaponizing mainstream progressive concerns to deliver positions that will reinforce the structural disadvantage and power imbalances already felt by the vulnerable groups they claim to have front-of-mind.

Take LGBTQ+ groups. Privacy and data rights campaigners will be justifiably quick to point to the importance of end-to-end encryption for queer communities living under repressive and homophobic regimes. Rightly so.

But it’s also the case that LGBTQ+ young people are at markedly higher risk of online sexual abuse, with young queer people being targeted and coerced precisely because of the inherent fragility and potential vulnerability of their situation.

Yet LGBTQ+ groups in the UK, Europe and the US are encouraged to see only unchecked end-to-end encryption as the way to guarantee their online safety. LGBTQ+ groups are encouraged to oppose sensible, purpose limited guardrails that could better promote the safety outcomes of queer teens in the U.K., EU and across the world, because of a largely hypothetical threat that client-side scanning could, might, theoretically be exploited by repressive regimes.

We see similar rhetorical tactics being deployed to drive a wedge between the interests of women and girls. Girls account for more than four-fifths of online grooming cases, yet women and girls are encouraged to reject safeguards to their personal safety because of the hypothetical possibility that scanning for child abuse could somehow be exploited by GOP-led states as part of their regressive rollback of women’s reproductive rights.

You might be surprised that it hasn’t occurred to the tech companies that their best response in this situation would be to stand up to the Republicans with the same vigour they’ve demonstrated in opposing legislation in the U.K. Instead, they’ve chosen to take the fight to children’s rights.

And still the list goes on. Almost remarkably, WhatsApp has produced a marketing video featuring the Afghan women’s football team to make a video implying their safety could be compromised by the passage of the Online Safety Bill.

WhatsApp has previously chosen to highlight the role of end-to-end encryption to tackle domestic abuse and tackle technology-facilitated forms coercive control (although its claims have been forensically and comprehensively unpacked by Refuge and other VAWG groups.) Yet while there is no explicit connection between client-side scanning to detect child abuse and anything that could undermine the safety of women being subjected to tech-facilitated domestic abuse, this still hasn’t stopped company PRs briefing precisely the opposite as part of their scare-tactic approach to build opposition to UK and EU Bills.

Across a range of vitally important progressive issues, tech companies and privacy activists are encouraging marginalised and disadvantaged groups to see a false dichotomy between their safety and well-being.

Marginalised groups are being encouraged to accept widespread, unchecked harm against their communities in order to avoid a set of theoretical risks and a never ending torrent of rhetorical slippery slopes.

It is staggeringly cynical behaviour, not least when some of the biggest advocates of this approach are self-styled progressive cheerleaders.

Don’t trust the experts, choose your own

Over many years those of us working in the child protection space have become all too used to seeing their concerns dismissed as a moral panic, with tech libertarian and data rights activists using language and framing to delegitimise child safety measures.

We’ve also seen the inveterate tendency among tech libertarians and privacy activists to frame online child sexual abuse as a societal problem, not a technological one.

This viewpoint is highly reductionist: the inconvenient truth is that the scale and complexity of online abuse has been actively facilitated by the poor design choices of tech firms. However, by developing a conceit that enables responsibility to be falsely externalised, this approach has enabled tech libertarians to continue to design their products in a way that contributes to harm, while building up ideological and unevidenced framing that technical solutions are unnecessary and intrusive.

And so the self-reinforcing logic goes on: tech-libertarian cybersecurity scholar Ross Anderson recommends the Online Safety Bill should be dropped in favour of increased funding for social services and child benefit payments for single parents.

Data rights groups continue to insist that we simply need to invest in user reporting, even though this ignores the lived reality of those who’ve experienced child sexual abuse; the consensus of expert opinion; and the coercive dynamics that mean that the overwhelming majority of online child sexual abuse is discovered not disclosed.

Meanwhile, Meredith Whitaker, the President of the messaging app Signal, claims that: ‘the idea that complex social problems are amenable to cheap technical solutions is the siren song of the software salesman.’

Having stated that she believed most abuse took place in the home and community, and so that is where the focus of efforts to stop it should be, she seems altogether less keen to discuss or be challenged on her views by child protection experts (or seemingly indeed anyone unless she can reply by quote tweet or inside a TV studio .)

Last year the tech industry made substantial strides in child abuse reporting, submitting 31.8 million reports containing over 88 million photos and videos. Strikingly, Signal didn’t submit a single one.

Seeking child protection opinions from this company’s leadership is the equivalent to seeking guidance on probity from Boris Johnson or tips from Carrie Bradshaw on how to dress down.

The progressive case for tackling child abuse

Let’s get one thing clear: online child sexual abuse is being driven by a systematic failure of safety and safeguarding by design. It simply isn’t the case that harm has just migrated from offline to online environments. Rather, we’re seeing a step change in which abusers have new opportunities to share, produce and organise child sexual abuse – inherently preventable harm that tech companies have chosen not to actively chosen not to prioritise.

Let’s also make clear that choosing to argue positions that actively expose children to unnecessary and inherently preventable risk isn’t an articulation of progressive values. It’s the antithesis of it.

I’ve always believed that children’s safety and well-being should be the cornerstone of progressive politics. It is morally and intergenerationally unjust to condemn children and young people to preventable harm that can trigger lifelong trauma, negatively impact their life chances, and adversely shape the adults they will become.

It is simply unacceptable to externalise the costs of selectively upholding fundamental rights onto today’s young people who will then be expected to navigate life while dealing with the aftermath and well observed impacts associated with adverse childhood experiences.

And it is as inappropriate as it is unsustainable to expect the growing bill for support to be placed on families, law enforcement and publicly-funded therapeutic and support services. Though it feels incredibly blunt to articulate the impact of online in purely financial terms, we know that online child sexual already costs the UK £2 billion each year. Those costs, however you choose to be measure them, will only continue to rise.

The emotional, psychological and economic cost of absolutism is one that no-one with a progressive outlook should ever be prepared to accept.

Big Tech is Big Tech, and their interests aren’t ours

One of the most noteworthy aspects of the end-to-end encryption debate is that privacy and data rights activists, propelled by keenly held and entirely justifiable concerns about the way in which Big Tech has used our data, may actually be perpetuating the market dominance of the largest companies – and in turn, may be creating the conditions for further abuses of market power.

The intentions may be progressive, but the unintended outcomes certainly aren’t.

It’s become increasingly clear that one company in particular, Meta, has been more than happy to fuel opposition to regulatory guardrails, with direct and indirect links to multiple civil society groups that have been quick out of the blocks to warn of the risks that client-side scanning could pose to the range of progressive use cases set out above.

It seems curious that many of these groups have not stopped to reflect on the reasons for Meta’s support, even more so when the company is on the one hand supporting privacy activists on E2E (fronted by Will Cathcart and WhatsApp), and on the other investing heavily in homomorphic encryption to enable it to continue to serve targeted ads to users even in a fully end-to-end environment.

The take-away? Meta doesn’t care about E2E, neither does it care about progressive use cases. But it certainly does see an opportunity to galvinise opposition to online safety bills and leverage legitimately-held concerns about privacy. The aim is to create a smokescreen where we’re all talking about end-to-end encryption and not the broader prize they really care about – seeing off the threat of antitrust action.

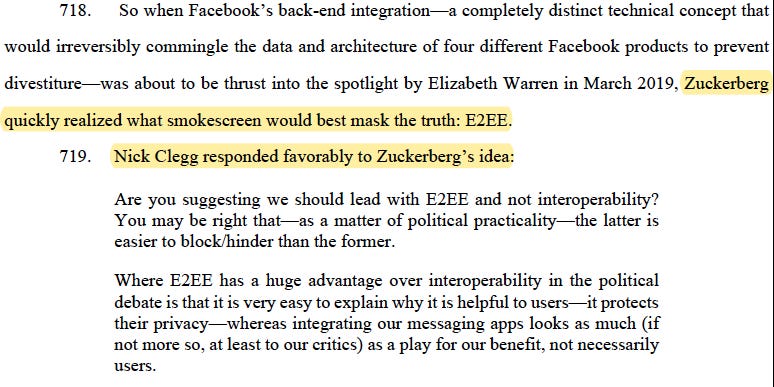

US court filings suggest that Meta has been quick to encourage a focus on E2E to distract from its real objective (see the telling extract from legal documents in a 2022 lawsuit below), bundling together its products into a single, interoperable backend. That, in turn, could actively frustrate if not render impossible any EU or US-based attempts at forced divestiture.

Progressive voices may be tempted to buy the arguments being made – but we should always follow the money.

And we should always reflect on why tech companies want to focus the debate in the carefully calibrated ways they do.